Frequently Asked Questions and Answers about ARKs

Basics

How can I give feedback on this document?

By inserting comments into this comment-friendly version.

What are ARKs?

ARKs (Archival Resource Keys) are high-functioning identifiers that lead you to things and to descriptions of those things. For example, this ARK,

https://n2t.net/ark:/67531/metadc107835/

gets you to a dissertation, and adding '??' on the end of the ARK should get you to its description:

https://n2t.net/ark:/67531/metadc107835/??

What's an identifier?

On the internet, an identifier is a URL, or part of a URL. For example, this core ARK identifier,

ark:/12148/btv1b8449691v/f29

appears inside two different URLs (Uniform Resource Locators, also known as web links or web addresses):

http://ark.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8449691v/f29

https://n2t.net/ark:/12148/btv1b8449691v/f29

ARKs are especially good at being persistent identifiers.

What's a persistent identifier?

The average lifetime of a URL was once said to be 44 days. At the end of its life, a URL link breaks, meaning it gives you the dreaded "404 Not Found" error that most of us have seen. Irritating as that may be, it's politically awkward when looking for publicly funded research, and it's a cultural disaster for libraries, archives, museums, and other memory organizations.

Among the many links that can or once could lead you to things, a persistent identifier is a link that in principle keeps working far into the future. Services that provide discovery and interlinking (such as between research articles, authors, supporting data, and related research) prefer persistent identifiers because of that stability.

Persistent identifiers should keep working even as things move between websites. Normally when things move, everyone who ever recorded the old links would need to be told what the new links are, which is next to impossible. That's where identifier resolvers come in.

What's a resolver?

A resolver is a website that specializes in forwarding incoming identifiers (the ones originally advertised to users) to whichever websites are currently best able to deal with them. Overall, forwarding is called resolution; one step in a resolution process is called redirection.

For a resolver to work, its hostname (the n2t.net or ark.bnf.fr in the identifiers above) must be carefully chosen so it won't ever need to be changed. Memory organizations, some of them centuries old, tend to have hostnames well-suited to be resolvers. Some well-known, younger resolvers are n2t.net (the ARK resolver), identifiers.org, doi.org, handle.net, and purl.org.

What kinds of things are ARKs assigned to?

To anything digital, physical, or abstract. That can include things that don't yet exist but to which you need to refer from objects that you're in the process of creating or planning, such as a link from a draft article to a dataset under preparation, or a link from an archived digital letter to a planned finding aid. One caution is that you should generally assign ARKs to things that you own, control, or manage. Assigning ARKs to things you don't control is discouraged because such identifiers tend to be fragile.

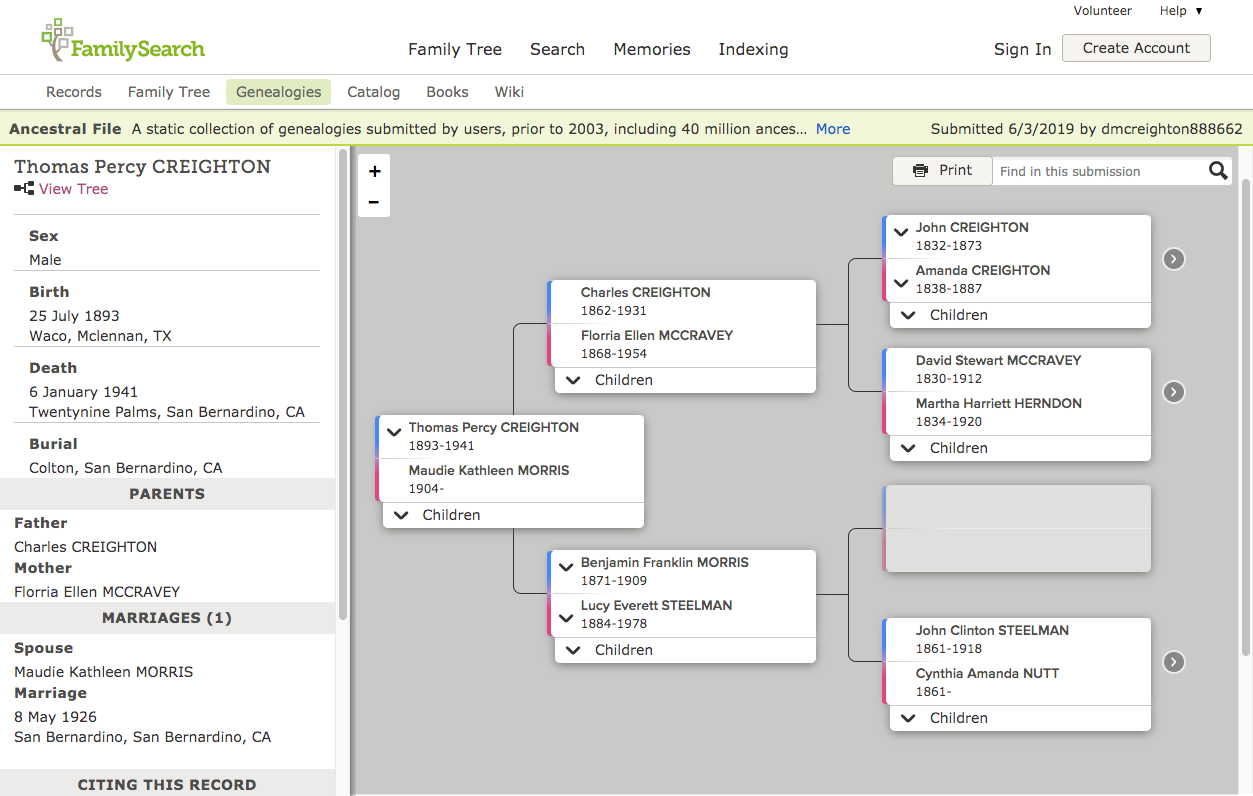

Kinds of things that have ARKs include those listed below. Numbers are approximate, current as of September 2019, and self-reported by the linked organizations.

Categories | Examples |

|---|---|

|

Who is using ARKs?

That's a little hard to say because ARKs are very decentralized, but more than 600 registered organizations have, between them, created an estimated 3.2 billion ARKs. You can find ARKs used as permalinks in

- the Data Citation Index (linked to the Web of Science),

- Wikipedia articles,

- Wikidata records,

- Internet Archive collections,

- ORCID researcher profiles, etc.

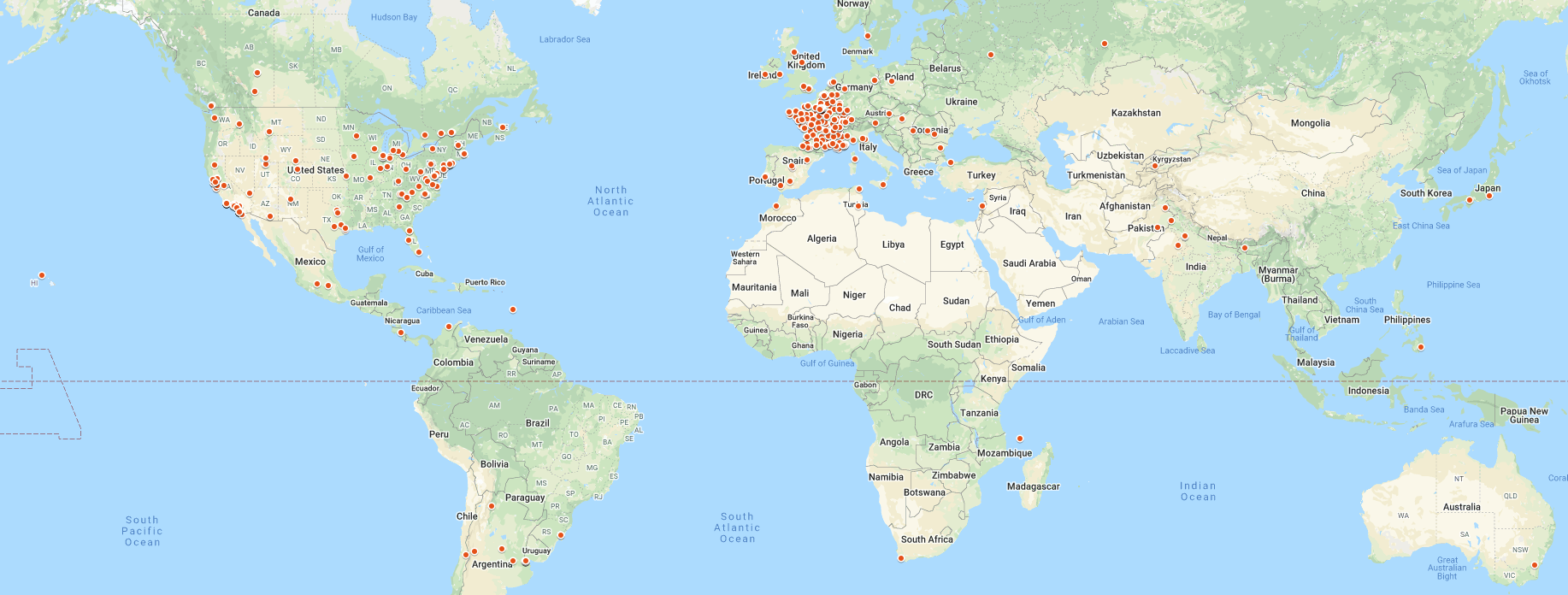

Here's the global distribution of organizations registered to create ARKs as of April 2020. Clicking on the static image below should take you to an up-to-date, zoomable map.

Getting started

What do I need to create ARKs?

First you need a NAAN (Name Assigning Authority Number), which is a number reserved exclusively for your organization. It must appear in every ARK your organization assigns, just after the "ark:/" label. The NAAN in all of these ARKs,

http://ark.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8449691v/f29

https://n2t.net/ark:/12148/btv1b8449691v/f29

is 12148, and it uniquely identifies the French National Library. Each NAAN is associated with the URL of a resolver for its ARKs, for example, to resolve 12148 ARKs, append them to http://ark.bnf.fr/ as shown in above. The N2T.net resolver is unusual in that it routes any ARK to the resolver registered under its NAAN.

There is no charge to obtain or use a NAAN, and you can request one by filling out an online form. Over 600 organizations have NAANs – libraries, archives, museums, university departments, government agencies, scholarly and educational publishers, projects, etc. – all listed in the public NAAN registry.

How do I start creating the character strings that become ARKs?

You are free to create ARK strings as you wish, provided you use only digits, letters (ASCII, no diacritics), and the following characters:

= ~ * + @ _ $ . /

The last two characters are reserved in the event you wish to disclose ARK relationships.

Another unique feature of ARKs is that hyphens ('-') may appear but are identity inert, meaning that strings that differ only by hyphens are considered identical; for example, these strings

ark:/12345/141e86dc-d396-4e59-bbc2-4c3bf5326152

ark:/12345/141e86dcd3964e59bbc24c3bf5326152

identify the same thing. The reason for this feature is that text formatting processes out in the world routinely introduce extra hyphens into identifiers, breaking links to any server that treats hyphens as significant.

What is the recommended form for ARK strings?

ARKs distinguish between lower- and upper-case letters, which makes shorter identifiers possible (52 vs 26 letters per character position). The "ARK way", however, is to use lower-case only unless you need shorter ARKs. The restriction makes it easier for resolvers to support your ARKs in case they arrive from the world with mixed- or upper-case letters, which happens regrettably often due to the lingering 1960's-era view that identifiers are case-insensitive (one sign of which is the prominence of the Caps Lock key on most computer keyboards).

Alphanumeric characters (letters and digits) are generally adequate, but it is recommended to use the betanumeric subset, consisting only of digits and consonants minus 'l' (letter ell, often mistaken for the digit 1):

0123456789bcdfghjkmnpqrstvwxz

This happens to be the repertoire produced from minters (unique string generators) supported by the Noid tool and N2T.net (used by ezid.cdlib.org and the Internet Archive), which creates transcription-safe strings using the strongest mainstream identifier check digit algorithm. When generating unique strings automatically, the absence of vowels helps avoid accidentally creating words that users can misconstrue.

Regarding assignment, one common strategy is to leverage legacy identifiers. For example, a museum moth specimen number cd456f9_87 might be advertised under the ark:/12345/cd456f9_87. Some legacy identifiers may need to be altered in view of ARK character restrictions. The second common strategy is to make up entirely new strings for your ARKs. In this case it is important to consider whether to make them opaque or non-opaque (or a bit of both).

What are opaque identifiers?

Persistent identifier strings are typically opaque, deliberately revealing little about what they're assigned to, because non-opaque identifiers do not age or travel well. Organization names are notoriously transient, which is why NAANs are opaque numbers. As titles and dates are corrected, word meanings evolve (eg, innocent older acronyms may become offensive or infringing), strings meant to be persistent can become confusing or politically challenging. The generation and assignment of completely opaque strings comes with risk too, for example, numbers assigned sequentially reveal timing information and strings containing letters can unintentionally spell words (which is why vowels are missing from the recommended character repertoire).

| Example strings with a range of opacity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| non-opaque | Netscape Permanent Archive | Gay_Divorcee_1934_April_1 | Name-to-Thing Resolver |

| opaque-ish | x0001, x0002, ..., x9998 | GD/1934/04/01 | n2t.net |

| opaquer | 141e86dc-d396-4e59-bbc2-4c3bf5326152 | 19340401 | n2t |

| opaquest | 141e86dcd3964e59bbc24c3bf5326152 | h8k74926g | 12148 |

ARKs are not required to be opaque, but it is recommended that the base object name be made opaque, since it tends to name the main focus of persistence. If any qualifier strings follow that name, it is less important that they be opaque. To help choose your approach to opacity, you may wish to consider compatibility with legacy identifiers and ease of string generation and transcription (eg, brevity, check digits). New strings can be created (minted) with date/time, UUID, and number generators, as well as Noid (Nice Opaque Identifiers) minters.

Opaque strings are "mute" and therefore challenging to manage, which is why ARKs were designed to be "talking" identifiers. This means that if there's metadata, an ARK that comes in to your server with the '?' inflection should be able to talk about itself.

How do I make server content addressable with ARKs?

First, decide what the user experience of accessing your ARKs will be, for example, a spreadsheet file, a PDF, an image, a landing page filled with formatted metadata and a range of choices, etc. Whichever you choose, plan for your server to be able to respond with metadata if your ARK should arrive with a '?' inflection after it.

Otherwise, serving ARKs is like serving URLs. Normally incoming URL strings somehow addresses (gets mapped to) content that your web server returns. If your server is ARK-aware, incoming ARKs (expressed as URLs) must be mapped to the same content. The term "map" here refers to a generic web server software process that associates the incoming URL with, for example, a particular file or a database entry. The process varies greatly across servers, but can be thought of abstractly as a lookup in a two-column table: column 1 for each incoming URL and column 2 for the corresponding file, database entry, or another URL.

Unfortunately, this mapping table description is abstract because the details depend on your web server software. Fortunately, however, it is very basic to how the web has worked since the 1990's and so doing your own resolution quite feasible. For example, most server configuration files can easily accommodate 100,000 mapping table rows with lines that look like "Redirect <incoming ARK> <URL on this or other server>" (columns 1 and 2, after you replace what is in <>'s). A common approach with ARKs is to map each incoming ARK (column 1) to the kind of URL that your web server already knows how to deal with, and you are done. With this approach, to keep the ARKs in column 1 stable you only need to keep the URLs in column 2 updated when they change. In this case your server is acting as a local resolver. If you don't want to implement this yourself, there are ARK software tools and services that can help.

Another approach is to run your web server without change, but instead of updating local tables, you would update ARK-to-URL mapping tables residing at a non-local resolver. Examples of this can be found among vendors and in any organization that updates tables via EZID.cdlib.org (which, due to a special relationship, updates resolver tables at n2t.net).

How do I cite or advertise an ARK?

The URL (https or http) form of the ARK is preferred, for example,

https://n2t.net/ark:/99166/w66d60p2

An ARK meant for external use is generally advertised (released, published, disseminated) in this way in order to be an actionable identifier. If a more compact visual display of an ARK is needed, it should be hyperlinked; for example, a compact display of an HTML hyperlink can be achieved with

<a href="https://n2t.net/ark:/99166/w66d60p2"> ark:/99166/w66d60p2 </a>

An important decision is whether your URL-based ARKs will use the hostname of your local resolver or the N2T.net resolver. If local control or branding is important enough, you would advertise ARKs based at your local resolver (see about serving content with ARKs). If you're concerned about the stability of your local hostname, you would advertise your ARKs based at n2t.net (see examples of both).

Resolving your ARKs through N2T is always possible for users, regardless of how you advertise them.

Are there tools and services to help with ARKs?

Here's a partial list of software tools for persistent identification that includes

- Noid (Nice Opaque Identifiers), open source software for minting and resolving ARKs on your own

- ArchivesSpace, open source application for managing and providing web access to archives, manuscripts and digital objects

- ARK plugin for Omeka, which creates and manages ARKs for the Omeka open source web-publishing platform

- ARK module for Drupal, which allows your Drupal site to act as a Name Mapping Authority (NMA)

There are also some vendors, such as ezid.cdlib.org, and some more information on concepts and best practices.

Beyond the basics

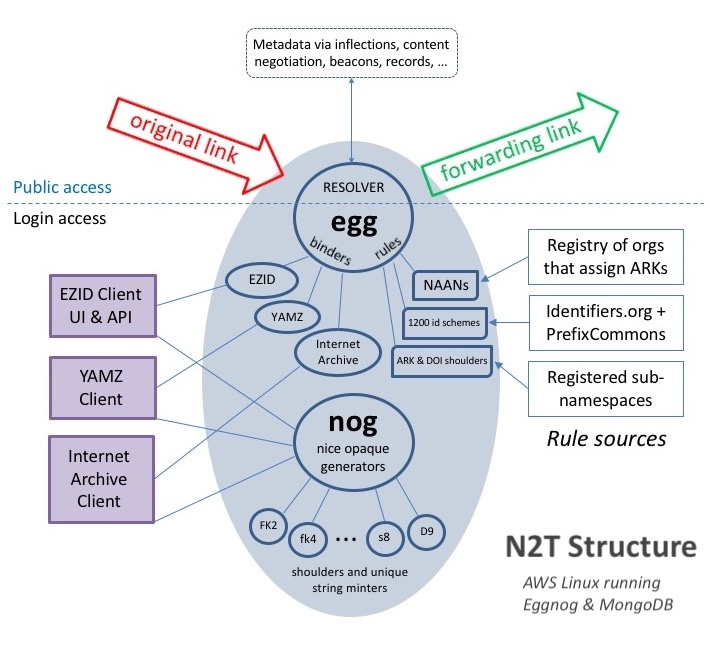

What is N2T?

N2T.net is a global ARK resolver. N2T, which stands for Name-to-Thing, is actually a generalized resolver for mapping names into things, so it knows where to route over 600 other types of identifier – ARK, DOI, PMID, Taxon, PDB, ISSN, etc. If you're interested, the diagram and the next answer give a bit more detail.

Resolution starts when someone attempts to access a URL (eg, by clicking on a link) consisting of "https://n2t.net/" followed by the identifier (name) to be resolved. As with any resolver, no one knows in advance – not the user, not the web browser, nor N2T itself – if resolution will be successful. It depends on what N2T finds that it knows about the received identifier.

When resolution is finished, the user is often unaware that it happened, unless they are paying attention (eg, they notice that the link in the location bar is different from what they clicked on). Resolution is designed to take place without the user noticing.

How does N2T do its work?

When a resolution request comes in from the general public, N2T looks up the identifier and redirects the original link to a forwarding link. To do this it uses two different resolution "patterns". To begin, N2T tries to resolve according to information found in an individual stored identifier. Failing that, N2T tries to resolve according to any stored class rules, based on the identifier type.

N2T has a different kind of stored data for each pattern. First, it stores individual records for about 50 million object identifiers (eg, ARKs, DOIs) that it obtains from three sources: EZID.cdlib.org, Internet Archive, and YAMZ.net. When such records include a redirection URL (target) and descriptive metadata, N2T can act on inflections as well as perform suffix passthrough and "content negotiation". To support creation and maintenance of individual identifier records, there is an N2T API requiring login credentials. The API also allows batch operations and unique identifier generation (minting).

Second, even if N2T knows nothing about an individual identifier, resolution may still work because of a stored routing rule record triggered by the type of the identifier. N2T maintains over 3500 rule records regularly updated from several sources, including the NAAN registry, a database of ARK and DOI shoulders, and a formal partnership on compact identifiers with identifiers.org.

If most ARKs run on their own resolvers, why is there also a global resolver for ARKs?

Most ARKs are created by organizations that advertise ("publish") them based at their own resolvers. For example, this ARK was published based at the ark.bnf.fr resolver:

http://ark.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8449691v/f29

Having to run and maintain your own resolver is the cost of complete autonomy. Using your own resolver also lets you do branding via the hostname, the downside being that brands are transient and tend to make identifiers fragile. Political and even legal (eg, trademarks) pressures may make supporting older branded hostnames, hence their identifiers, difficult.

That's another reason for having the global ARK resolver. People coming across a broken identifier in the future may find its hostname no longer exists, and if it's an ARK they can extract the core identity (starting with "ark:") and present it to the global n2t.net resolver, as in

https://n2t.net/ark:/12148/btv1b8449691v/f29

My organization has its own ARK resolver – should I care about N2T.net?

Yes, for two main reasons. First, if your ARKs "in the wild" show up without your resolver hostname (meaning that they start "ark:...", which is not uncommon to see), the person wanting to use them won't need to know the hostname as long as they can remember to add "n2t.net" in front of them. This works because N2T knows the correct resolver hostname.

Second, while some organizations and their resolver hostnames are long-lived, most are not. A person trying to use an ARK containing a non-working resolver hostname can replace the non-working part with "n2t.net". If circumstances ever force you to change your resolver, this replacement step gives ARKs that you published prior to the change a better chance of working. In some cases, an organization itself may be long-lived, but for legal or political reasons it may be required to change its hostname.

To avoid future inconvenience, some organizations that run their own resolvers may choose from the outset to suppress their resolver names and just advertise ("publish") their ARKs based at n2t.net.

Why does the global ARK resolver (n2t.net) not have the word "ARK" in it?

When demand for a global ARK resolver arose, basic principles of openness and generality prevented the designers from creating yet another silo in the DOI/Handle/PURL mold. Instead, the ARK resolver was built to be a generic, scheme-agnostic resolver called N2T (Name-to-Thing), which now resolves over 600 types of identifier, including ARKs, DOIs, Handles, PURLs, URNs, ORCIDs, ISSNs, etc. Resolution is essentially looking in a table for an identifier string, regardless of type, and redirecting it to the right place.

The same basic principles guided the design of an earlier tool called noid, which was built for ARKs but is also regularly used by organizations that mint Handles.

What does "suffix passthrough" mean?

Briefly, suffix passthrough is a feature of N2T. Suppose you have only one registered ARK, https://n2t.net/ark:/12345/6789, and it redirects to the web server page,

https://a.example.org/dataset542

And suppose that same server also serves up these pages:

https://a.example.org/dataset542/volume3https://a.example.org/dataset542/volume3/part2https://a.example.org/dataset542/volume3/part2.pdf

What suffix passthrough does is to let your one registered ARK act as if you had also registered these three ARKs below, which would resolve to the pages above, respectively:

https://n2t.net/ark:/12345/6789/volume3https://n2t.net/ark:/12345/6789/volume3/part2https://n2t.net/ark:/12345/6789/volume3/part2.pdf

In this case, suffix passthrough saved your having to maintain registrations for three more pages. In fact, it works for an unlimited number of pages.

What are the parts of an ARK?

ARK ANATOMY

Resolver Service Base Object Name Qualifiers

__________________ _________________ _____________

/ \/ ... \/ \

https://example.org/ark:/12345/x54xz321/s3/f8.05v.tiff

\_________/ \__/ \___/ \______/\____/\_______/

| | | ... | | |

| Label | | | Sub-parts Variants

| | | |

Name Mapping Authority (NMA) | | Assigned Name ...

| +---------- Shoulder: /x5

Name Assigning Authority Number (NAAN)

Can I assign ARKs to things inside something that already has an ARK?

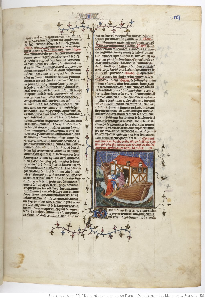

Yes, ARKs can be assigned at any level of granularity, such as to a manuscript, to chapters inside it, to chapter sections, subsections, etc. An ARK can also be assigned to a thing that encloses other things. In ARKs the character '/' is reserved to help the recipient understand about containment, for example, the first object below contains the second:

ark:/12148/btv1b8449691v

ark:/12148/btv1b8449691v/f29

That's the containment qualifier. There's only one other ARK qualifier, and it indicates variant forms of a thing by using the reserved character '.' in front of a suffix. For example, if these ARKs identify documents,

ark:/12148/btv1b8449691v/f29.pdf

ark:/12148/btv1b8449691v/f29.html

because they differ only by the suffix .pdf or .html, it can be inferred that they identify two different forms of the same document.

What is the purpose of the NAAN?

By obtaining a NAAN, an organization gets the exclusive right to create ARKs "under" that NAAN. Your NAAN is part of a prefix in front of all your ARKs. The set of ARKs you can create is infinite and is known as your NAAN's namespace, and your NAAN namespace is a sub-namespace (subset) of the ARK namespace (the set of all possible ARKs). For example, the Internet Archive's NAAN namespace is all ARKs starting with "ark:/13960/". NAANs effectively subdivide the ARK namespace into non-overlapping sub-namespaces, each one holding an infinite number of possible ARKs. Since organizations only create ARKs in their own namespaces, ARK assignments between organizations do not conflict.

NAANs play a key role in resolution. For example, if a resolver cannot find an incoming ARK in its database, it looks at the incoming NAAN and redirects the ARK to the local resolver registered with the NAAN. This is precisely what the N2T.net resolver does. Any local resolver could be configured to return the favor for any incoming ARKs with NAANs that it doesn't know about, simply by redirecting them to N2T.

How do namespaces work?

Namespaces and sub-namespaces work on the principle that whenever a prefix defines a namespace, it only needs to be "extended" (adding characters to the end of the prefix) to create a new sub-namespace directly under it. The sub-namespace also contains an infinite number of possible ARKs. There is potentially a namespace associated with every prefix.

| Set of all ARKs starting | Namespace defined | Example ARK in that namespace |

|---|---|---|

ark:/ | All ARKs | ark:/99999/fk4gt2m |

ark:/12345/ | ARKs under the NAAN 12345 | ark:/12345/p987654 |

ark:/12345/x5 | ARKs under the 12345/x5 shoulder | ark:/12345/x5wf6789 |

ark:/12345/x5wf6789/ | ARKs under the 12345/x5wf6789 object | ark:/12345/x5wf6789/c2/s4.pdf |

Examples like those in the above table are quite common. The first is for all ARKs and the second is for all ARKs under ark:12345. The third is the shoulder concept, described below, which is the next subdivision under the NAAN; note that it has no "/" after it. The fourth, a complete ARK-as-prefix example, shows that an object ARK is itself also a namespace, with potentially an infinite number of "sub-ARKs" that descend from it to name object parts and variants. The practice of creating new namespaces by adding information to an existing namespace is very common and very old, for example, in "snail mail" terms, you might be from Springfield or, more precisely, Flat #3B, 4321 Main Street, Springfield, Ontario, Canada.

What is a shoulder?

A shoulder is a sub-namespace under a NAAN. It is the set all ARKs starting with a short, fixed extension to the NAAN. For example, in

the shoulder, can be designated by /x5 if the context is clear, but it is often best to use its fully qualified, globally unique designation of ark:/12345/x5. In the classic namespace tradition, the shoulder is the set of all possible ARKs starting with the long shoulder name.

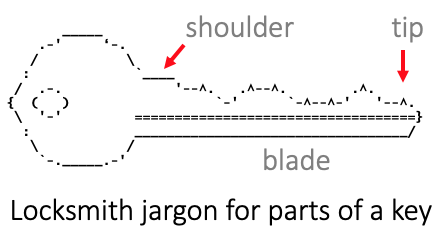

Note that while the shorter shoulder name (the extension to the NAAN) is set off from the NAAN by a "/", it is not followed by any separator character that marks the end of the shoulder. Our use of this term is borrowed from the locksmith profession, which understands sets of keys to be defined by fixed (unvarying) "shoulders" that precede the varying shapes ("blades") that follow it.

What is the purpose of a shoulder?

Shoulders help organize a NAAN namespace. Just because it contains an infinite number of possible ARKs does not mean that finding an unassigned ARK is easy.

A shoulder is analogous to a guest room in your house. Imagine a colleague, Sally, who takes in a long term lodger, Larry. Sally's home is extremely spacious (in fact it is infinite), but Sally complains that Larry leaves things permanently lying around all over the house: his coat on the kitchen chair, glasses on the dining table, book on Sally's desk, slippers next to the sofa, coffee cup on the bathroom sink, etc. By the terms of his lodging agreement, Larry's things, once placed, cannot be moved. But Sally, who also needs room for things and might – one never knows – take on new lodgers, is stuck forever noticing and checking not to disturb Larry's stuff. You shake your head in sympathy, but quietly plan that should you ever take in a long term lodger (an independent assignment operation under your organization), the lodging agreement would set aside a guest room (a shoulder) with the requirement that the lodger's things can only be placed in that guest room. Under such an agreement, Larry's stuff would have left all of Sally's home undisturbed except for the one room set aside for Larry, and she could then easily take on any number of new lodgers under similar agreements.

So shoulders allow ARK assignment operations under a NAAN to be delegated to autonomous projects or divisions, just as NAANs do under the overall ARK namespace. Even if an organization initially only wants to use ARKs for one project, plans may change. If other needs for ARKs arise later, setting aside a new shoulder for each new project or division makes it easy to ensure that autonomous assignment streams – present, past, or future – won't conflict with each other, thanks to non-overlapping namespaces. (Shoulders can also ease the namespace splitting problem.)

Why is there no "/" to mark the end of a shoulder?

In other words, in an ARK such as ark:/12345/x5wf6789, why is the shoulder "/x5" not followed by a "/"? According to ARK rules, if you had published

(please don't do this) ark:/12345/x5/wf6789/c2/s4.pdf

the "/" after "/x5" implies

- that

ark:/12345/x5is also an object and - that the object named

ark:/12345/x5/wf6789/c2/s4.pdfis contained in it.

Both are likely untrue, at least in any way that can be easily explained to a user. It may seem natural to add a "/" because it makes the shoulder boundary obvious to in-house ARK administrators. Recalling that in-house specialists can afford to be inconvenienced, it doesn't help the end user either is uninterested and confused by your internal operational boundaries, or is so very interested that you risk their trying to hold you to account for their inferences (eg, about consistent support levels across objects sharing the apparent containing object). Less transparency about administrative structure hides messy details and can save you user-support time in the end.

In fact, in-house ARK administrators always know where the shoulder ends, provided it was chosen using the "first-digit convention". A primordinal shoulder is a sequence of one or more betanumeric letters ending in a digit. This means that the shoulder is all letters (often just one) after the NAAN up to and including the first digit encountered after the NAAN. Another advantage of primordinal shoulders is that there is an infinite number of them possible under any NAAN.

How do I implement a shoulder?

There are different ways to implement a shoulder. Fundamentally, a shoulder is a deliberate practice based on a decision you make to assign ARKs that start with a particular extension to your NAAN. A shoulder can then "emerge" as your practices consciously observe and incorporate that extension as a prefix in ARKs that you create.

Having said that, there are a couple of cases where shoulder implementation does involve a kind of "creation" step. A system such as ezid.cdlib.org supports both the purely "decision-based" shoulders above (that emerge from user practice, eg, Smithsonian) as well as the creation of system-recognized shoulders with accompanying minter services and registered API access points. In contrast, implementing a decision-based shoulder requires no explicit shoulder creation step, but does involve the creation of one or more ARKs that start with that shoulder. As a special case that works with the N2T.net resolver, it is possible to create a short ARK, such as ark:/99152/p0, that is an identifier even though it looks and acts like a shoulder due to suffix passthrough.

A completely different kind of shoulder "creation" step is needed to implement a shoulder under one of the few shared NAANs (below).

Are there restrictions on the use of NAANs and shoulders?

Yes. It is important never to invent or use a NAAN that is not listed in the public NAAN registry. In general ARKs that an organization creates always start with its NAAN, but exceptions are made for four special NAANs meant to be shared across organizations. To avoid the possibility of conflicting ARK assignments on a shared NAAN, the simple solution is for organizations to reserve a shoulder by filling out the usual form to request a shoulder under a shared NAAN.

Each shared NAAN has certain immutable connotations that software (and people with enough training) can recognize and benefit from.

| Shared NAAN | Purpose, meaning, or connotation of ARKs with this NAAN | Expect to resolve? | OK for long term reference? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Example ARKs appearing in documentation. They might resolve, but no link checker need be concerned if they don't. They should never be used for long term reference. | maybe | no |

| ARKs for controlled vocabulary and ontology terms, such as metadata element names and pick-list values. They should resolve to term definitions and are suitable for long term reference. | yes | yes |

| ARKs for people, groups, and institutions as "agents". They should resolve to agent definitions and are suitable for long term reference. | yes | yes |

| ARKs for test, development, or experimental purposes, often at scale. They might resolve, but no link checker need be concerned if they don't. They should never be used for long term reference. | maybe | no |

The 99999 and 12345 ARKs are especially useful if you are responsible for reviewing broken link reports because they can all safely be ignored. Despite providers' best efforts, these test and example ARKs frequently "escape into the wild" for all to see. Recipients (eg, people and link checkers) that would normally be concerned with broken links have only to recognize these two special NAANs in order to not become distracted by such ARKs.

Is there a quick way to get started creating test ARKs?

Yes. Instead of reserving a 99999 shoulder, if your organization already has its own NAAN, you can immediately create and use a "quick test ARK". This is an ARK that starts with ark:/99999/9NNNNN_, where NNNNN represents the NAAN (preceded by '9' and followed by '_'). There is no need to register a quick test namespace since it is automatically set aside for each NAAN. As with any prefix, there is an infinite number of possible test ARKs in each NAAN's quick test namespace. Two versions of an example quick test ARK belonging to the BnF (NAAN 12148) are

https://ark.bnf.fr/ark:/99999/912148_testxyz

https://n2t.net/ark:/99999/912148_testxyz

Note that N2T.net is configured to forward any quick test ARK it receives (second version above) to the appropriate local resolver (first version).

Can I make changes to a NAAN or a shared shoulder?

You can change the registry entry for a NAAN by filling out the same online form used for requesting a new NAAN. For security purposes requests are processed manually. Example reasons for a change may include

- notifying N2T of a change in your organization's contact person or resolver URL,

- updating your organization's name assignment policy (sample policy),

- requesting an additional NAAN, eg, to support a significant new body of ARKs or new organizational division, and

- transitioning your NAAN to another organization that will carry on your work and future use of your NAAN.

NAANs are portable. If your organization transitions into or out of a vendor relationship, there is no impediment to taking your NAAN with you.

ARKs and other identifiers

Why would I use ARKs compared to, for example, DOIs?

- To keep costs down (details).

- To work with exactly the metadata you want.

- To be able to create identifiers without metadata.

- To be able to create an identifier even before your object exists.

- To have an identifier as soon as you create the first draft of your data.

- To hold that identifier private while the data and metadata evolve, and decide (maybe years) later, to publish or discard it.

- To retain that identifier upon publication, perhaps then assigning an additional identifier, such as a DOI.

- Because ARKs, built for generic application and not specifically for published content, fit naturally with physical objects like samples or field stations.

- Because ARK resolvers can deal with identifiers routinely damaged out in the world by text formatting processes that introduce hyphens.

- Because most ARKs carry a Noid check digit that can be used to detect all common transcription errors rather than just some of them.

- To be able to create shorter identifiers, since mixed-case permits denser strings (a larger number of strings of a given length).

- To be able to change vendor and/or infrastructure without having to coordinate database transfers with a central authority.

- To be able to deal with the namespace splitting problem without losing control of your identifiers.

- To link identifiers to different kinds of nuanced persistence commitments.

- To be able to add queries (eg, ?lang=en) when resolving your identifiers.

- To use open infrastructure consistent with your organization's values.

- To link directly to the objects you value instead of to landing pages.

- To create one identifier that enables millions (suffix passthrough).

- To access convenient, full-function metadata via inflections.

- To integrate easily with IIIF APIs using ARK qualifiers.

What do ARK, DOI, Handle, PURL, and URN have in common?

These are the major persistent identifier types (or schemes).

- All have been in existence since 2001 or before.

- All are found in places like the Data Citation Index ℠, Wikipedia, and ORCID.org profiles.

- All give access to almost any kind of thing, whether digital, physical, abstract, person, group, etc.

They also have very similar structure, as seen in the examples below, consisting of four parts:

https://n2t.net/ark:/99999/12345 |

|

And they all have little effect on persistence. See 10 persistent myths about persistent identifiers.

Wait, are you saying ARK, DOI, Handle, PURL, and URN are useless?

No, that's too strong a statement. But let's keep these identifier schemes (types) in perspective.

- They all fail to stop the major causes of broken links: loss of funding, natural disaster, social upheaval, war, deliberate removal, human error, and provider neglect.

- They all require you, the end provider, to update forwarding tables as URLs change.

- They all identify content that is subject to change or removal on future visits.

- They all have identifiers that break regularly and in large numbers – many thousands and more.

- They all rely on ordinary redirection built in to web servers since 1994 and provided for free by hundreds of URL shortening services.

Given how little the schemes do for you, when choosing one you'll likely want to consider factors such as cost, risk, and openness.

How do ARKs differ from identifiers like DOIs, Handles, PURLs, and URNs?

The short answer

ARKs are the only mainstream, non-siloed, non-paywalled identifiers that you can register to use in about 48 hours. DOIs, Handles, and PURLs require resolution and other services to come from their respective centralized systems (silos).

That's not to say that persistence is free. Making any identifier persistent burdens you, the provider, with the costs of content management, hosting, monitoring, and forwarding. You can do those things yourself or with help from a vendor. But with ARKs, just as with URLs, you will not be charged separately for your identifiers and you will not be locked in to a special-purpose resolution silo that also locks out other identifiers.

ARKs are unusual in being decentralized. While one can get resolution services from a global ARK resolver called n2t.net, over 90% of the ARKs in the world are published without without using n2t.net in the URL hostname. More than 600 registered organizations across the world have, between them, created an estimated 3.2 billion ARKs, and, as with URLs, no one has ever paid an identifier fee to create them. Of course maintaining them isn't free. It is never without cost to keep content access persistent in the long term, regardless of identifier type.

More differences between ARKs, DOIs, Handles, PURLs, and URNs

- Landing pages: Crossref and DataCite DOIs link to publisher landing pages constructed around but not directly to objects you care about, but ARKs can freely link directly to objects you care about, which is machine- and human-friendly since it does not require an extra human navigation step for common tasks such as

- opening an article's PDF file for reading,

- referencing an image file meant to be incorporated automatically inline into a document, and

- citing a spreadsheet to be used for direct data analysis by software.

- DOIs, Handles, etc. do not support ARK-style inflections.

- that permit access to metadata regardless of whether an identifier points to an object or its landing page.

- Unlike DOIs and Handles, ARKs don't have metadata requirements. ARKs that haven't been released into the world are easy to delete.

- All things eventually pass, including hostnames and the web itself and the "

https://"protocol. When that first part of the identifier ceases to have meaning, only ARKs and URNs will include the label (eg, "ark:") indicating the type of identifier that remains. - For DOIs, Handles, and PURLs, you are required to use their respective resolvers. ARKs and URNs, permit you to use your own resolver.

- To create DOIs and Handles, you are required to pay a membership fee and, for DOIs, there are per-DOI charges passed on in various ways by allocating agencies. There are no fees for ARKs, PURLs, and URNs.

- To create Handles, you are required to install and maintain a local Handle server, which gives you another system to monitor, patch, and troubleshoot.

- Although you can use a local or vendor resolver for your ARKs and URNs, ARKs can be resolved via the global n2t.net resolver.

- The envisioned URN resolution infrastructure was never built, so URNs are currently resolved as URLs, and there is no designated global URN-as-URL resolver. In order to register to create URNs, you must apply for a URN namespace.

- ARKs have some unique features that support early object development: ARKs can be deleted, can be born with no metadata, and can exist with any metadata you care to store.

But if ARKs can be deleted, how can they be trusted?

It actually makes ARKs more trustworthy. The ability to delete is a vital part of healthy collection management that is denied to those non-ARK identifier types prohibiting deletion under the presumption that people, once they are asked to commit, won't make mistakes. People armed with identifier management software regularly turn simple human errors into large-scale mistakes, even at the threshold of commitment. By making it difficult to clean them up, we force systems to drag those messes forward in perpetuity.

While not immune to such mistakes, ARKs have the big advantage that they can be created and deleted in the shadows, independent of release, publication, or archival commitment.

Can an object have both an ARK and a DOI?

Yes. Sometimes having two identifiers is useful, although it can become confusing when it happens often. Many people start by assigning ARKs to each thing they create in order to have a stable reference right from the beginning, even before they know whether they want to publish it, let alone keep it.

The object and its metadata develop together, and for the subset of things that you end up wanting to publish in places that require DOIs, you can assign DOIs at publication time. If your ARK is stable and has basic metadata, you're already doing everything you need to support a proper DOI. This is a way in which ARKs support early object development.

To support two identifiers efficiently, it is recommended that you create the DOI such that it redirects to the original ARK. This not only eliminates the need ever to update the DOI redirection, but it also keeps the ARK persistent for anyone who previously recorded or bookmarked it.

When should I use ARKs compared to DOIs, Handles, PURLs, or URNs?

There are no simple answers. Identifiers (not things, but their names) are tricky to talk about, so if you hear simple answers elsewhere, beware of common fallacies.

Nothing inherent in ARKs, DOIs, Handles, PURLs, or URNs makes them more or less fit for any particular field, domain, or sector. With an identifier resolver and administrative management service, they all provide the core service of resolution (and so do properly managed URLs).

Generalizations about identifier types sometimes apply when resolution and management for that type is locked into one particular vendor or provider. For example, many PURL and Handle features and restrictions are well-defined by their respective administration silos, as are those of DOIs, which are built on top of Handles. But DOIs have metadata practices that are diverse and evolving across different DOI registration agencies.

The concrete differences that we experience, such as metadata, landing pages, and tool integration (eg, publishing tools), are not properties of identifier schemes per se, but properties of resolution, management, and citation services that various providers extend to or withhold from different identifier types. Those services are shaped in turn by communities of practice and by markets. Basic services are founded on a reliable database storing each identifier along with metadata elements (creator, title, date, redirection URL, etc) that describe the identified object. Extra services include link checking, duplicate detection, report generation, and searching.

From cradle to grave

When in my workflow should I create ARKs?

At object birth, or even before. We sometimes name our babies before they're born, and we name and refer to objects in the conception stages, sometimes long before they bear fruit. Depending on how elaborate the planning may be, your unborn objects could have full-function ARKs that resolve to an appropriate surrogate and return rich metadata, including persistence statements.

The only caveat is to be careful releasing (advertising) ARKs that have uncertain long term prospects. Some identifier management systems have features to help manage and resolve unreleased identifiers (eg, EZID has a "reserved" status). The more people who know about an ARK, the harder it is to delete.

How is it that ARKs can be easy to delete?

If no one knows about an identifier but you, there's no harm in deleting or withdrawing it. Stepping back, an identifier is actually an assertion that a given string of characters is associated with specific thing. The fewer people you tell, the easier it is to scrap that assertion. If you create a URL and share it only with your closest colleagues, that is much easier to withdraw than if the URL appeared for a month on a public website, from which it was harvested by internet search engines. In contrast, it is hard to delete DOIs and Handles because once registered and made resolvable, they are effectively released to the world.

ARKs behave like URLs in this respect. Providers are free to create and share ARKs narrowly, in which case they're easy to delete.

Perhaps surprisingly, even if shared more broadly, ARKs should come with persistence statements that tell you how much or how little commitment is made to them. ARKs were designed to articulate a variety of persistence statements, but they are certainly not alone among identifiers and objects that exhibit a variety of commitment "flavors". This is why ARKs are known as high-functioning identifiers that are good at persistence rather than as "persistent identifiers".

Finally, people make mistakes. ARKs, DOIs, Handles, PURLs, and URNs are sometimes broadcast in error and need to be withdrawn. When that happens, provider best practice is to make the withdrawn identifier resolve to a "tombstone" page that explains and perhaps apologizes for the inconvenience. Despite the rumors, persistent identifiers are never guaranteed.

What is meant by ARKs supporting early object development?

People need identifiers before they know exactly what object they refer to, or if they refer to anything worth keeping. An identifier that requires mature metadata cannot be created during early development since little is known about the object. So object creators almost always initially assign identifiers that have no metadata requirements, such as URLs or ARKs.

If you start with an ARK, you benefit from being able to keep the original identifier through to public release as the metadata matures. Many objects go through intensive development and revision phases, sometimes lasting years, during which they are too immature to meet most metadata requirements. Nonetheless every object needs some sort of identifier from conception to maturity, where maturity could look like public release and further enhancement, or abandonment. It is easy to abandon ARKs that have not been released into the world.

Like the object itself, metadata elements need a flexible place to grow and mature over time:

- starting in the planning phase, when it just needs an identifier,

- at the moment of birth, when its first digital representation needs a redirection target URL,

- after the first analysis, when its significance and a tentative title emerges,

- when creating dozens of discipline-specific metadata elements that violate most metadata standards except your own,

- during post-processing by a colleague whose name you will add as an additional creator,

- when early feedback based on the tweeted identifier turns up a key insight and a new contributor,

- and so forth, through to archiving, abandonment, public release, correction, revision, enhancement, etc.

Unlike Crossref and DataCite DOIs, which require specific metadata (eg, see the DataCite schema), ARKs do not constrain any of these activities. Moreover the N2T.net resolver actually supports all of them.

If ARKs don't require it, why bother creating metadata?

Creating metadata (extra information associated with or describing an object) has several key benefits. First, no matter what the ARK redirects to – whether a landing page or a file – metadata gives users vital information about the object, such as references to newer versions, creation date, provenance, etc. For ARKs typically metadata is accessed via

Metadata really eases the difficulty of working with opaque identifiers, which reveal no clues as to what they identify. In the absence of metadata you are forced to access the object itself to remind yourself what it is, and also to trust that you're accessing the correct object. Moreover, discrepancies between returned metadata and the accessed object help everyone detect identifier changes and errors.

Metadata is for grownups, and is far less important for immature objects and their identifiers than for those that have been released. Having metadata demonstrates basic provider credibility and commitment to high-functioning identifiers. Not every provider is up to this task.

It need not be expensive. Building metadata from scratch can be costly, but it's usually created and managed by object providers, in which case it can be leveraged efficiently for identifiers. Ideally, for strong persistence master metadata (maintained by object providers) should be reflected in independent systems so that it is hard for someone to tamper undetectably with identifier associations. For example, digital object repositories that obtain ARKs and DOIs from the EZID service store a copy of their metadata with EZID.cdlib.org, which in turn stores another copy with the N2T.net resolver.

What metadata is recommended for ARKs?

Metadata is messy business for all identifiers, not just ARKs. Across domains and object types there are thousands of standards, many of them overlapping yet conflicting, and each is applied according to local organizational customs and with varying levels of compliance. Choosing or creating a specification for your metadata depends on factors such as

- whether you are currently managing metadata (hint: stay with it unless you have a good reason to switch),

- whether you want to officially publish objects (hint: prepare to be able to supply author, title, date, publisher/archive, and object type),

- the requirements and capabilities of your resolver (hint: your IT staff or vendor might have its own requirements), and

- whether you want to store non-standard elements (hint: N2T allows this, but most standards and vendors don't).

Reliable cross-domain interoperation may remain out of reach, but Dublin Core, DataCite, Schema.org, and Dublin Kernel are common metadata specifications to consider for use with ARKs.

Why do I see ARK metadata with who, what, when, where labels?

ARKs were designed to identify anything, not just things that are, for example, publishable or purchasable. It is unnatural to model a fossil, tissue sample, vocabulary term, or Marie Curie as if each has an Author, Title, Publisher, Copyright, and Price. Instead, since 2001 an ARK typically has a four-element kernel of highly generic metadata (Dublin Kernel, inspired by Dublin Core (DC)), followed by any other metadata elements (name/value pairs) the provider wishes to provide.

Kernel metadata is structured as if in answer to the questions, who, what, when, and where regarding the expression of, or the "telling" of, an object:

- who "told" it (similar to DC Creator, Contributor, and Publisher, but also Inventor, Discoverer, Conductor, etc),

- what the "telling" was called (similar to DC Title, but also TissueSampleNumber, ArtifactBarcode, etc),

- when it was "told" (similar DC Date, but includes date ranges, approximate and BCE dates),

- where the "telling" can be found (from DC Identifier, but usually not needed because this is the ARK itself)

There's much more to say about ARK metadata, for example, applying who, what, when, and where to the content of a biography, or how an archive plans to support a dataset. More ARK metadata guidelines will be made available at arks.org. Other elements are key, such as

- how it was "told" (similar to ResourceType), which may dictate mappings to external metadata specs and additional elements

- redirection target URL, which is usually stored as a distinguished element of metadata

- elements holding persistence statements, to express the strength or weakness of an archival commitment

What is an ARK "inflection" and how does it differ from "content negotiation"?

An inflection is a change to the ending of a word to express a shift in meaning. It permits us to define a word such as "go" without also defining "goes" and "going". To an ARK that leads to an object, simply adding a '?' to the end (the '?' is one example of an ARK inflection) permits us to request metadata without having to define a separate identifier for the object's metadata. This simple technique can be used by a human with a web browser. The N2T resolver supports both inflections and content negotiation.

Content negotiation for metadata is a software technique for requesting alternate formats of an object, such as the PDF or RTF form of an HTML file. Although not designed for it, historic "content negotiation" was kludged (twisted) in certain contexts to request metadata under the startling assumption that formats often used to hold metadata are in fact metadata and will never be objects in their own right. Unlike inflections, "content negotiation for metadata"/doesn't work at all for objects represented in those formats (the list of which is growing and known only by private agreement), nor is it easy enough to be used directly by most human users.

Although inflections are commonly associated with ARKs, they are not "owned" by ARKs. Contrary to popular belief, identifiers don't do anything – it's their resolvers that do or don't support such features. So, for example, inflections and suffix passthrough are supported by n2t.net for all identifier types, but not by doi.org or handle.net (which has a related functionality called Template Handles) for any identifier types.

What do you mean by silos?

Typically, scheme-based services are designed as silos, or closed platforms, serving a particular identifier type such as Handle, DOI, or PURL. Each silo performs the same main functions – mapping names (identifiers strings) to things (objects or metadata). Excluding all but one type of identifier string may help to capture markets, but it's wasteful and non-inclusive. It requires building the same set of services over and over for each type and violates basic principles of openness.

In contrast the N2T (Name-to-Thing) resolver and EZID (identifiers made easy) management interface were designed to work with all identifiers. Effort put into any new feature can be efficiently leveraged across all types, which sometimes creates surprising flexibility. For example, ARKs are often stored in EZID with "DOI metadata", and every DOI stored in N2T can benefit from "ARK resolution features" such as inflections and suffix passthrough, which are not available via the main DOI resolver (doi.org).